Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies present opportunities for government in all sectors. Beyond automation, 4IR enables the integration of physical, digital and biological potential to enhance human capability well beyond current limits.

The potential impact is huge, and is already being felt: development is happening ten times faster than during the first industrial revolution, and at roughly three hundred times the scale. When considering this against the understanding that law and public policy is informed by societal norms and expectations that build over time, one quickly realises that governments may need to move faster on 4IR.

Mature public policy is needed to shape and enable 4IR technologies for mutual benefit while protecting our communities from harm or exploitation. Active policy making must also allow for proactive consideration of ethics and the development or adaptations of laws that govern its use within societal expectations. One technology at the forefront of international attention from a public policy perspective is Artificial Intelligence (AI).

What is it?

AI is the theory and development of computer systems or computer-controlled systems that can copy intelligent human behaviour.1

A simple example is a computer playing a game of chess or driving a car. The system can employ machine learning (ML) by synthesising large datasets and algorithms emulating human learning to become more accurate in predicting outcomes without being explicitly programmed to do so. Facial recognition works on this principle. Further, where ML is still reliant on human input of data sets, the use of ‘deep learning’ is the use of unstructured or limitless datasets in various forms (images, text, graphics) to allow the system to inform its own algorithm. This reduces the reliance on manual human intervention and is the beginning of ‘strong AI’ and sentient machines.2 Whilst Hollywood portrayal of sentience in blockbusters such as The Matrix, Terminator and Ex-Machina give light to the possibilities of human-machine collaboration (and its potentially devastating consequences), the current considerations for the use of AI are far more grounded in the everyday concerns of humans and societal impacts.

So what does this have to do with public policy?

We hold humans to account for their behaviour in society through a set of rules founded in the basic social contract that belies governance in human society. Governments use public policy to satisfy the social contract in response to a specific issue of public interest. The objective of public policy on any given issue is to set the trajectory of development for the benefit of society and to address problems encountered by society through guidelines, principles, rules and other governance mechanisms.

Public policy considerations with regards to AI and ML are complex and multi-faceted. The balancing of protection and promotion of AI requires the government to make conscious decisions on the regulatory and policy landscape for AI.

- One approach is to look at existing laws and policy and how we use technology to ensure compliance with these boundaries. An example of using existing laws would be interpreting provisions in existing international law to the application of lethal autonomous systems in the context of armed conflict and undertaking an Article 36 weapons review.3

- An alternative is to adjust our legal, regulatory and policy boundaries to accommodate changes in the use of technology. An example of amendments to existing law is amending privacy legislation (Privacy Act 1988) to account for privacy consideration of data-matching across government agencies.

- Thirdly, governments may seek to introduce new legislation and regulations with regards to technologies that have such a distinct and profound effect that their use can no longer be informed by existing legislation. The Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 is an example of creating new legislation and regulatory requirements to address an existing gap specifically, mandatory cyber security incident reporting. Further, the Australian Government’s Blueprint for Critical Technologies identifies current and emerging technologies that have been identified as having a significant impact on our national interest (defined as economic prosperity, national security and social cohesion). One of the categories is AI, computing and communications.4 While this Blueprint does not regulate, it does educate developers, users and the public in some of the additional broader contextual understanding of the application of the technology, and some of additional risk management that may be required or prudent.

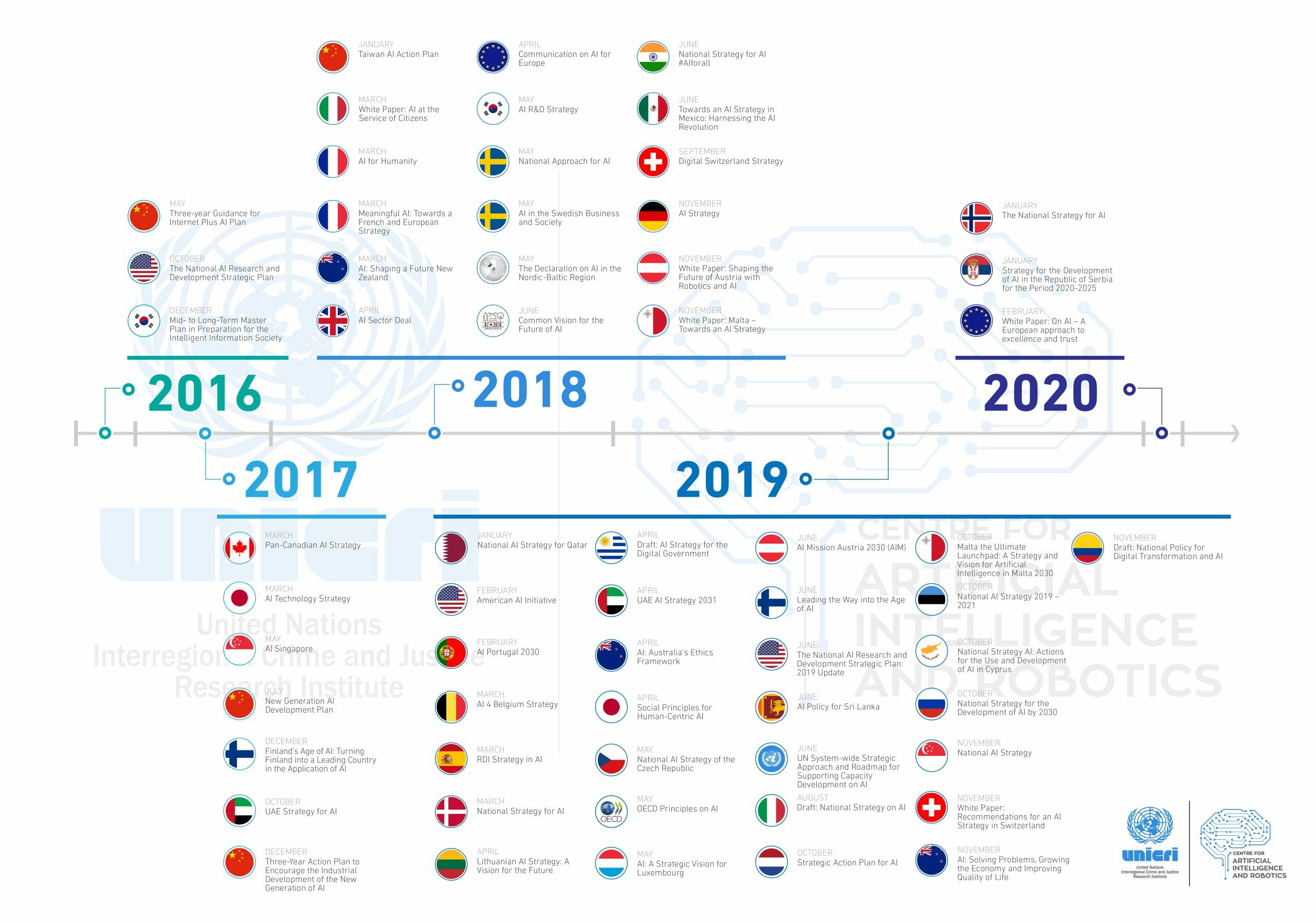

The following timeline is indicative of the international pathway of foreign governments towards regulation and policy, including an acknowledgement of the ethical considerations that underpin such public policy decisions. The move towards greater public policy in the field of AI is a recognition of the duality of the benefit-risk of the technology. Notably, the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute opened a Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in the Hague in September 2017 in order to raise awareness and educate policy-makers and government officials from member states.

Practical policy considerations for AI systems

The following table presents a high-level non-exhaustive list of practical public policy considerations for AI.

| Issue of concern | Considerations | Policy response vector |

|---|---|---|

| Accountability | Who is accountable for loss or damages caused by the system. Particularly those that could not be foreseen by the manufacturer or programmer. This is an increasing risk with the introduction of deep learning and autonomy in AI systems. | Legal/ Regulatory |

| Control and compliance | What controls are programmed into systems to reduce the risk of harm or unintended consequences. This may include automated systems that have effect in Australia but are controlled outside of Australian jurisdiction for financial reasons or a permissive legal environment. Functional and fit-for-purpose compliance regimes are also an integral part of a regulatory system. | Regulatory/ Policy |

| Displacement of workers | The replacement of unskilled labour in process jobs replaced by AI. The replacement of skilled professionals where robotics, AI and other 4IR technologies provide cognitive decision-making abilities. | Social/ Legal |

| Bias or discrimination | Systemic and repeatable errors in a computer system that create unfair outcomes. For example – Robodebt scheme – automated debt assessment and recovery by Services Australia 2016. | Legal/Regulatory/ Social |

| Privacy | Ensuring that Privacy laws and regulation simultaneously allow for protection of privacy and informed consent for the owners of the information/ identity. This is particularly the case where a system can aggregate a large amount of data that would identify an individual where they would not otherwise be identified. Conversely, being able to use this information for law enforcement and national security purposes. | Legal/ Social |

| Data Security | Ensuring that custodians of AI technology and datasets provide adequate levels of data security. As this technology develops, the use of large data sets is becoming a tradeable commodity. It is used by companies, organised crime, social media and foreign governments to derive information for exploitation. Aside from the privacy and informed consent issues raised above, there is a gap where privacy meets cyber security in requiring data security. | Legal/ Regulatory |

How do we best position ourselves for the future?

There is a plethora of information that exists on what other nations and the international community is doing following the recognition that regulation and public policy are now necessary for human-centred AI systems but also as AI systems and deep ML move towards sentience.

IBM have published a set of principles and corresponding pillars of risk-based AI governance policy. These are accountability, transparency, fairness and security. They are principle-based guidance that relies on trustworthiness of systems and their custodians. This is a good place to aim but first the Australian Government should give consideration of how we wish to employ AI and other 4IR technologies as a government, a public service provider and a facilitator of infrastructure in various sectors, including finance, healthcare, defence, law enforcement, national security, and robotics. What benefits can we derive and what harms do we seek to mitigate. Additionally, the application of the technology will dictate the regulation. We may be seeking the ability for lethality in an automated system for military use and the avoidance of injury in system that looks and feels similar but distributes aid in areas of natural disaster. Similarly, systems that have both commercial and law enforcement applications require public policy considerations that may elicit different regulatory requirements.

The current legal and regulatory frameworks are piecemeal and designed primarily around protection of privacy or cyber security threats to government or critical infrastructure. To satisfy yourself that any AI applications are within the regulatory parameters for their intended use requires a comprehensive understanding of multiple areas of regulation both state, federal, foreign and international. A more comprehensive examination of AI public policy from an enabling, risk management and governance perspective would position Australia and the Australian Government to harness the opportunities of new technology and minimise undesirable or harmful use. In the meantime, there are a growing number of technology law and public policy professionals that are able to advise on legal, public policy and ethical considerations that support the use of 4IR technologies, including AI.

About the author

Briony has over 20 years of experience working for the Australian Government in national security, international security, defence and transnational crime.

Briony delivers valued legal advice and general advisory work on sensitive and high-profile matters and has led successful policy and capability initiatives.

Briony has strong representational and negotiation skills, having worked, or presented in various international fora and committees.

Briony is skilled in analysing information from a strategic viewpoint, identifying all risks, challenges and limiting barriers.

Briony holds a number of degrees including a Master of Laws from the Australian National University and a Master of Politics and Policy from Deakin University.

Briony is a presiding member on the Legal Aid Review Committee of the Australian Capital Territory.

Briony is a graduate of the Australian Institute of Company Directors and is a board member of a charitable organisation invested in providing educational and vocational outcomes for Indigenous youth.

When not engaged in her children’s sporting activities, Briony enjoys training at the gym, being on the water and going on adventures with her family and friends.

References

- Oxford dictionary

- www.ibm.com

- Article 36 of the 1977 Additional Protocol to the 1949 Geneva Conventions

- www.pmc.gov.au