An integrated public service is vital to cultivating collaboration, enhancing efficiency and improving the delivery of services to the Australian public.

With increasingly complex and tailored service delivery comes a need for government to collaborate across portfolios, levels of government, and with our trade and security partners internationally. Important regulatory environments that provide parameters for the activities of the public service can either directly or indirectly, and rightly or wrongly, create barriers for effectiveness.

Knowledge of these barriers, and strategies to better navigate them, will help public servants to best support the Australian community.

What is an integrated public service?

An integrated public service is one which promotes collaboration, communication, data-sharing, joint problem-solving, improves cost-efficiency and can help to identify systemic problems. When departments work together effectively, it can reduce costs, avoid duplication and improve outcomes for Australians.

Consider sector-scale workforce planning, for example health workforce planning, and the integration required to fully understand the supply and demands of suitably skilled persons, now and into the future. Relevant datapoints span immigration, education, and public health domains at the federal level, and hospitals, health administration at the state/territory level, and possible roles for non-government organisations such as peak bodies and professional associations.

An integrated public service would allow for the collection, storage and transfer of this data seamlessly within and across public services.

Regulatory barriers preventing cohesion

Instead, we often find officials, agencies and entire governments caught in the doldrums of regulatory barriers that inhibit integration, particularly with respect to data sharing.

Officials are concerned about a myriad of obligations they, their agencies, and the broader government are beholden to, and the easier option is to turn away from integration. The inverse is also possible, where poorly planned integration leads to inadvertent breaches of obligations.

Datapoints are duplicated across government in lieu of integration, with subtle variations enough to undermine their credibility. Without supporting data, important decisions may be put on the backburner while other more easily defensible (and possibly less impactful) policies and programs are progressed.

We see isolated instances where integration is enabled, but it’s not the general practice and the foundations that enable the integration are not scalable or repeatable.

Barriers to integration

Many barriers link back to the regulatory operating environment that public servants are operating within. For example:

- Strict agency processes developed following a breach which overly constrain the activities of public servants.

- Reduced risk appetite from an agency due to perceived reputational, business or legal risks.

- Complex and varied legal agreements that lead to downstream hesitation or inability to share critical information.

- ICT system design and implementation that fails to consider valuable inputs or outputs in the broader system.

- General risk-averse attitude within the agency.

These common issues are symptoms of a key underlying problem. While not all of these barriers are strictly regulatory in nature, they are in some shape or form underpinned by a regulatory environment that isn’t working for the agency, and is preventing improved integration.

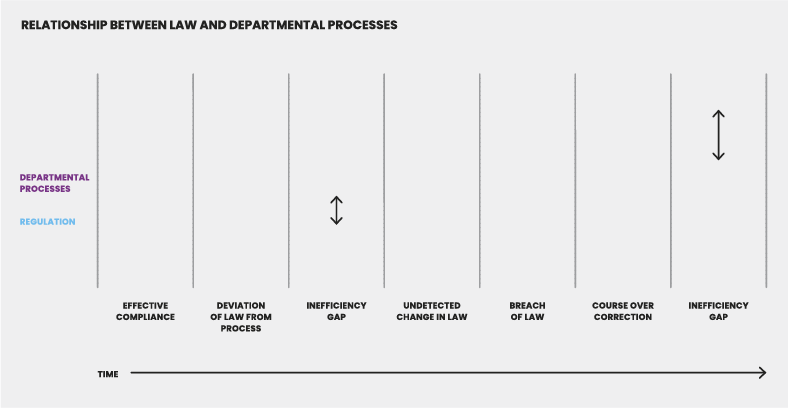

An example of this at play is the interaction between departmental processes and the underpinning regulation.

These factors can result in the development of processes and protocols which may be more burdensome than the regulation itself. Whilst compliance with legislation by the government is vital, it is worth considering that frequently, our experience shows that government departments may establish operating procedures that adopt a position on organisational risk that limits the agency’s ability to benefit from the underlying regulation’s parameters. These risk-averse protocols hamper integration and result in avoidable losses of efficiency.

Additionally, as the law changes, if departments do not have their finger on the pulse, undetected regulatory changes may lead to inadvertent breaches of the law. This can lead to a knee-jerk overcorrection in processes to avoid subsequent breaches, which further increases their burden on operations.

“Once bitten, twice shy.”

The diagram below demonstrates this typical interaction.

Using regulation as the foundation of improved integration

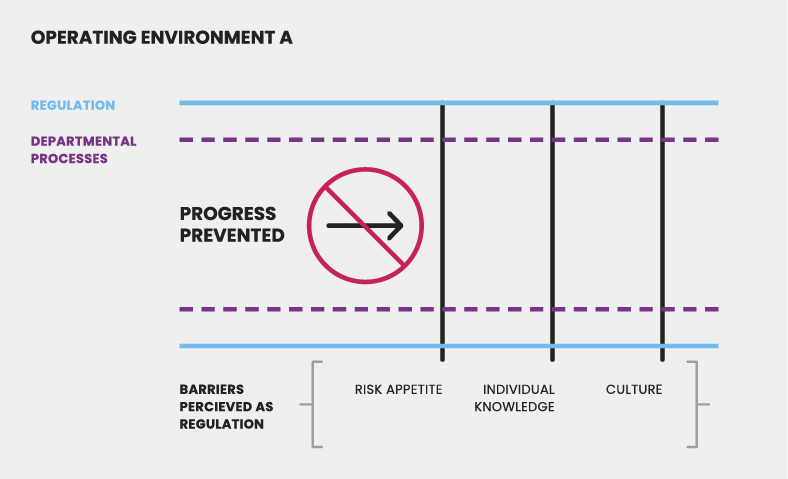

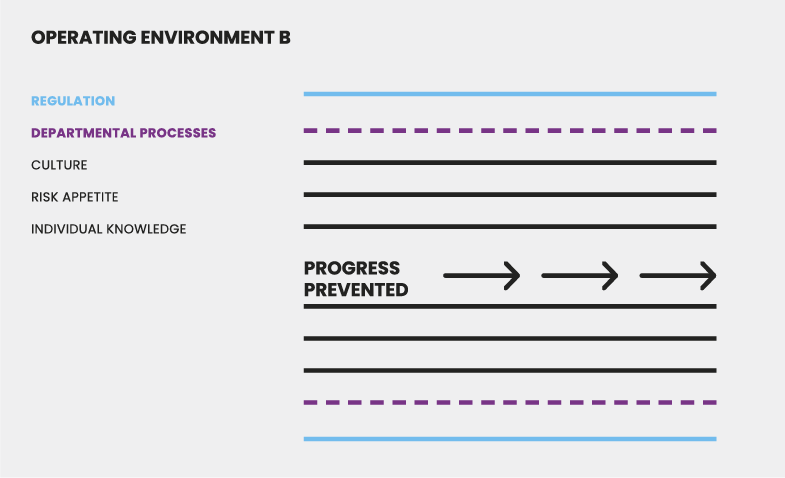

There is an opportunity for the same “barriers” to be used as alignment principles to create an authorising environment for improved integration. Conceptually, it’s about moving from Operating Environment A (top) to Operating Environment B (bottom):

We’ve seen improvements in agencies that undertake the following in line with their regulatory operating environment(s):

1. Capability uplift—knowledge building in key integration functions to understand the operating environment and right-size their risk appetites to the regulatory reality.

2. Policy and process redesign—removing unnecessary checks and balances that reflect outdated regulatory settings or risk appetites.

3. Assurance—implementing deliberate checks and balances across agencies and industries where law change could result in a change in operating environment.

Takeaways

Regulation isn’t a barrier; it’s an operating environment to be navigated. Lean into the hard work up front and reap the rewards of a better integrated public service. Proximity has helped agencies to undertake the required analysis of the regulatory operating environments impacting specific initiatives and entire sectors, and has helped to design and implement reform to support a better integrated public service.